Analytics

Analytics

Commentary: ROI is the only KPI

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are one of the hottest topics in product management (well, management in general in a well run company). However, many struggle in defining meaningful ones. I assert there’s only one that matters: return on investment (ROI). Using this will help simplify and clarify all your activities and planning. I have found few things that can’t be defined in terms of ROI.

In my work across a variety of companies large and small I typically see one of these situations:

- KPIs inherited from what finance/sales (or whomever the revenue generating owner is) says measured as pure P&L and not often reconciled with the total investment (and often missing secondary KPI product and user success measures)

- A massive number of intricate measures that no one can get their head around nor really knows how or why each matters for the business/product

- Not much at all

In each case, there needs to be a KPI reset. I encourage most teams I work with to have primary and secondary KPIs. Primary are what really defines and measures success. Secondary are more intricate that focus on more detailed aspects of a product or business. I have arrived at the point — after testing this across many different types of products, services and organizations — that ROI (broadly applied) is the one all products should set as their primary KPI.

In my teaching, we discuss these KPI categories:

- Acquisition: how do customers discover the product

- Conversion: how to we get them to pay

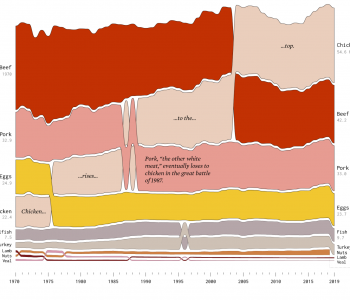

- Engagement: how regularly and for how long your product is used

- Retention: when time to return/renew, do they

- Satisfaction: how do customers rate the product

- Defect rates: what is the rate of defect/failure in the product

- Cost savings: how can this product make the business more efficient

There are a few KPI models but most overlap with these groups. These are excellent secondary KPIs and should be measured in every product. In addition, we always want to measure our KPIs in terms of our customer needs, not just our business interests.

Amazon provides one of the best example here: typically, warehouse logistics would measure success as the time from order received until order shipped. Amazon measures from order received until customer receipt of the package. If they are quick in the warehouse but the shipper is slow their customer still is not satisfied. This is also why you see Amazon taking over the last mile of deliveries more and more.

All traditional KPIs can be translated into ROI. Let’s look at some examples.

Example: Social network engagement

Social networks are all about engagement, right? Well, yes, that’s a key secondary measure: typically daily active users (DAU) over monthly active users (MAU). However, every user and every user interaction has a value. Facebook makes money on ad display and interaction. They know the values of those and a bit of math can peg a value on each user engagement. They then need to know both what are the upfront and ongoing R&D for the service plus other operational costs providing the ROI denominator. That might seem simple and obvious but there’s a knock-on effect: by tracking ROI, they can actually see variations that engagement alone does not show. What if ad rates fluctuate? What about bandwidth or R&D costs? What if we now need to hire 20,000 people to moderate our content? Engagement alone is too simple.

Example: Subscription service retention and LTV

Its less expensive to keep a customer than acquire a new one goes the saying (and the data most often supports this). This one should be pretty straightforward as any good acquisition engine inherently uses ROI to evaluate their marketing spend efficacy. But what about retention? How much are you willing to spend (often in discounts or other incentives) to keep a subscriber? Companies typically know the lifetime value (LTV) of their customers (especially if you’re in the subscription game). Its the average purchase * typical retention period purchases (e.g. $30/mth over 15 months or $450 LTV).

However, are you tracking lifetime net profit (LNP) of your customers? LNP takes LTV and considers margin. Continuing the example above, if we consider that we have a 33% margin on those subscriptions, our LNP is actually $148.50.

| Lifetime Net Profit per User | |

| I. Avg Purchase | $30 |

| J. Average Purchases per month | 1 |

| K. Typical retention (months) | 15 |

| L. LTV (IxJxK) | $450 |

| M. Average Margin | 33% |

| N. LNP of a user (LxM) | $148.50 |

When the marketing dept tells customer service that they can spend $200 to incentivize a customer to stay, that might actually be a negative ROI.

Example: Real customer acquisition cost

Any good marketer (esp digital) will track the ROI of all their placements across media buys. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) is typically your marketing spend (for a given channel/placement) over your number of conversions. But just looking at CAC might not show the full picture. Consider the example below:

| Real Customer Acquisition Cost | |

| A. Marketing Spend | $10,000 |

| B. Clicks | 2,000 |

| C. CPC (A/B) | $5.00 |

| D. Conversion Rate | 2.5% |

| E. Conversions (BxD) | 50 |

| F. CAC (A/E) | $200 |

| G. Discount on 1st purchase | $50 |

| H. Real CAC (F+G) | $250 |

The conventional CAC does not capture the fact that there’s also an incentive discount of $50 making the real CAC $250.

If you want to take it further, the LTV/CAC ratio is often measured as key to tracking unit profitability. Combining our two examples above, this would be 2.5x ($450/200) under the conventional model. But considering LNP/rCAC, that now is a negative 0.59x ($148.50/250) return. It looks like you have a nice ROI on your marketing spend for your service and a good retention plan, but maybe not.

Thus, using ROI (or its proxy measures) is going to give you a clearer picture of:

- Is what I’m doing operationally with my product profitable?

- Is my acquisition funnel profitable?

- Should I build this?

I now always ask this question and drive to find these ratios when I engage companies on product strategy.